Introduction – Things at Penn: The Social Lives of Near Eastern Objects at the University of Pennsylvania

by Heather J. Sharkey

Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania

What can we learn from objects?

In the late nineteenth century, when many of the great art, archaeology, anthropology, and natural history museums of the United States were taking shape, American scholars believed that objects could “speak” to people. Even immigrants who knew little English could benefit from viewing the curated materials that hung on walls or stood in glass cases. Objects, the assumption ran, had the power to convey knowledge and civilization.[1]

Founded in 1887, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (more commonly known as the Penn Museum) embodied these ideas about civilization in the very layout of its building. During the museum’s early years, visitors entered the museum and then went downstairs to study the remains of “primitive” societies as represented, for example, by Native American materials or by items from Borneo. By contrast, visitors ascended stairs to reach the archaeological collections of the ancient Near East and Egypt, which were meant to represent “advanced” though long-lapsed civilizations.[2] Their elevated position in the museum was no accident, for in the United States at the time, the Near East and Egypt commanded tremendous prestige as cradles of Judeo-Christian religion and as the setting for events recounted in the Bible.[3]

Over time the Penn Museum acquired some of its objects through donations or direct purchases. But the bulk of its collection came from Penn’s archaeological efforts abroad, which began in 1888 with excavations at the Mesopotamian site of Nippur (now in Iraq). The Penn Museum thereafter sponsored a series of other expeditions at sites that are now in Iran, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, and elsewhere. The dating of these sites ranged from the sixth millennium BCE to the thirteenth century CE, that is, from the late Neolithic age into the Islamic era. By receiving allotted shares of unearthed materials, Penn amassed huge collections in decades that followed. This process of collection came to a standstill around 1970, when Penn signed the UNESCO convention on the preservation of cultural property.[4] Henceforth, Penn scholars continued to participate in archaeological excavations to the Near East and Egypt but did so without bringing “loot” back to Philadelphia.

Today, the Near Eastern and Egyptian collections at the Penn Museum remain a tangible legacy of a late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century era when objects represented both research materials and cultural trophies for the museums that owned them. Moreover, at a time when Penn was still establishing its reputation as a preeminent American research university within the United States, acquisitions enhanced Penn’s prestige.[5] To be sure, Penn claimed to be old by American standards. Official histories traced its beginnings to 1740, when the institution began as a charity school for poor Philadelphia children. (This charity section lasted well over a century and only closed in 1871 when Philadelphia committed itself to educating all the city’s children.) Penn even claimed the distinction of having established the first medical college in the United States in 1765. And yet, when the museum began in the late 1880s, Penn was only just becoming involved in systematic laboratory research, in archaeology as well as in fields like biology and chemistry.[6] The Penn Museum thereby helped to burnish Penn’s reputation during this formative period when U.S. universities were developing at high speed as research centers, and not only as teaching colleges.

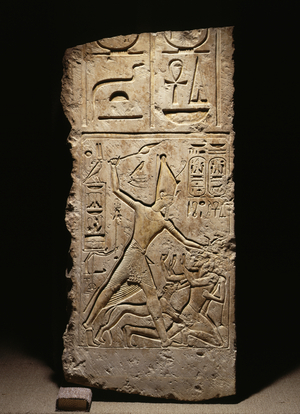

The Penn Museum also helped to enhance the reputation of the United States as a “player” in the Middle East. As the nineteenth century ended and the twentieth began, the U.S. government claimed steady consular representation in the major cities of the Ottoman Empire and Iran, while American Protestant missionaries (many of them from Philadelphia) had a strong presence in the region as well, as founders of modern schools, hospitals, and printing presses.[7] And yet, the United States was not yet a “Great Power” in the region on a par with France, Britain, Russia, or even Germany. Penn’s digs in places like Nippur (Iraq) and Memphis (Egypt) enhanced the reputation of the United States in this age when an archaeology race, akin to an arms race, was running strong, but with the stockpiling of antiquities rather than weapons as the goal.[8] Amidst the “scramble for the past”, Penn’s acquisition of royal objects (such as the statue of the Egyptian pharaoh Amun carved sometime between 1332 and 1292 BC; or the headdress of the Sumerian Queen Pu’abi from Ur, circa 2400 BC) established the United States as a custodian of and successor to ancient civilizations.[9]

As heirs to the university’s history of engagement in the Middle East, students in the Fall 2014 seminar entitled “Here and Over There: Penn, Philadelphia, and the Middle East” (NELC 133) looked closely at Penn’s collections, in the Penn Museum as well as in Van Pelt Library, the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, the University Archives, and elsewhere on campus. They considered things that Penn is now preserving for posterity, such as ceramic pots, archival documents and photographs, gold jewelry, and even human remains. They read and discussed works like The Social Life of Things, a 1986 book edited by the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai, which was the result of a conference at Penn.[10] Appadurai and his colleagues argued in this volume that objects like Persian rugs and medieval Christian saints’ relics have had “social lives” and have acquired meanings and values through movement, use, and exchange.

After examining materials in Penn’s collections, students began to ask their own questions about the social lives of “Penn things”. For example, one inquired, by studying a 4,500-year-old silver flute from the Royal Cemetery at Ur (Iraq), what can we discern about the musical culture of the people who made and played it? What can we learn, too, from museum records about the curators who first misidentified this flute as a precious-metal drinking straw of the kind that Mesopotamian royalty had once used to sip their beer? Alternately, another asked, what can we learn from considering the Penn Museum’s loan records for an eight-hundred-year-old, illuminated Koran manuscript that has “travelled” widely to appear in exhibits at Penn, elsewhere in the United States, and abroad? How would its original owner have used this Koran, for devotional purposes; how do observers, admiring its rich illustrations, look at it now? More broadly, how have materials and technologies of literacy informed textual cultures? Students in the seminar realized that this question is as relevant for a Sumerian cuneiform tablet (including one that recounts a flood narrative reminiscent of the biblical story of Noah) as it is for a fifteenth-century Persian love poem penned on paper in a period when Iran was a center of paper-making technology (while Europeans, by contrast, were still writing on parchment, that is, on prepared animal skin).

Through conversations with curators, the students in this seminar became aware of issues in the politics of collecting, the cost and mechanics of preservation, and the practicalities of research. They started to ask questions such as, “How did we get such-and-such an object?”; “Do we have the resources to preserve it?”; and even “Can we investigate it in new ways?” The students learned that a 6,500-year-old skeleton from Ur, which was resting in a big box on a backroom shelf for decades, answered this last question with a loud yes in 2014, as technological advances made it possible for museum researchers to analyze the remains of this person – a tall male of about fifty years old – in new ways. Having visited the storage room for the Near East collections, the students also developed an understanding of the choices that a museum must make in deciding what goes on display and what stays in the basement – and how the stuff that stays in the basement can have deep value for research. They saw, for example, the storage collections of cylinder seals of the kind that Mesopotamian people used for thousands of years to “sign” their packages in clay, and hopefully to make them tamper-proof until they reached their destinations. The students began to appreciate, too, how the images carved into the stone of each cylinder seal – pictures of deities, humans, and other creatures, as well as features of natural landscapes and geometric motifs – can offer insights into Mesopotamian art, religion, and culture.

What can we learn from objects or things? We can learn about histories of everyday life, art, religion, and politics, whether long ago, when the things in question came into being; or in recent times, when archaeologists dug them up or the museum acquired them. We can understand changing human values and priorities, as they relate, again, to an object’s makers, users, excavators, curators, or viewers. We can learn in the process about the institution – to be precise, our institution – which has preserved, arranged, and interpreted its collections for public display or for research behind closed doors. Objects “speak” if we ask the right questions, and they have many stories to tell.